At what point do accommodations for our kids become the very thing that stunts them?

Flexibility. Accommodation. Modification. Grace. Those are good things, right? At face value I would say that, yes, of course they are. We are living in unprecedented times, so it stands to reason that there are necessary adjustments to be made. To our way of thinking. To our daily habits. And to our familiar routines. The expectations placed on us legislatively and societally have changed, therefore, so too must we. However, at what point do accommodations for our kids become the very thing that stunts them?

This is the first year, of my 21 years in public education, that I have had the privilege of working with high school students. While the kids I am around now may be older and taller than I’m used to, the impact I am seeing on them is similar to that of younger students, and why wouldn’t it be? Over the past two years school aged children (whether elementary, middle, or high school) have had to adjust to:

- Wearing masks

- Increased health screenings and safety protocols

- Modified engagement with peers and staff

- Classroom restructuring

- Alternate/modified curriculum

- Changing academic criteria

- Reductions or limitations in extra-curricular activities

- Fewer traditional supports

…to name a few.

All of that is not easy and it is not fun. It has had negative implication on students, parents, and staff alike. It has been difficult, frustrating, and at times has even felt futile. Due to all the life changes and new demands brought about by the pandemic, we have had to make adjustments. We have created accommodations in an attempt to mitigate the challenging circumstances, both great and small, heaped on our kids. You may be thinking, of course we have. We should be making accommodations during this anomalous time. While I agree (to a degree) I think it’s important that we also ask ourselves, at what point do accommodations for our kids become the very thing that stunts them?

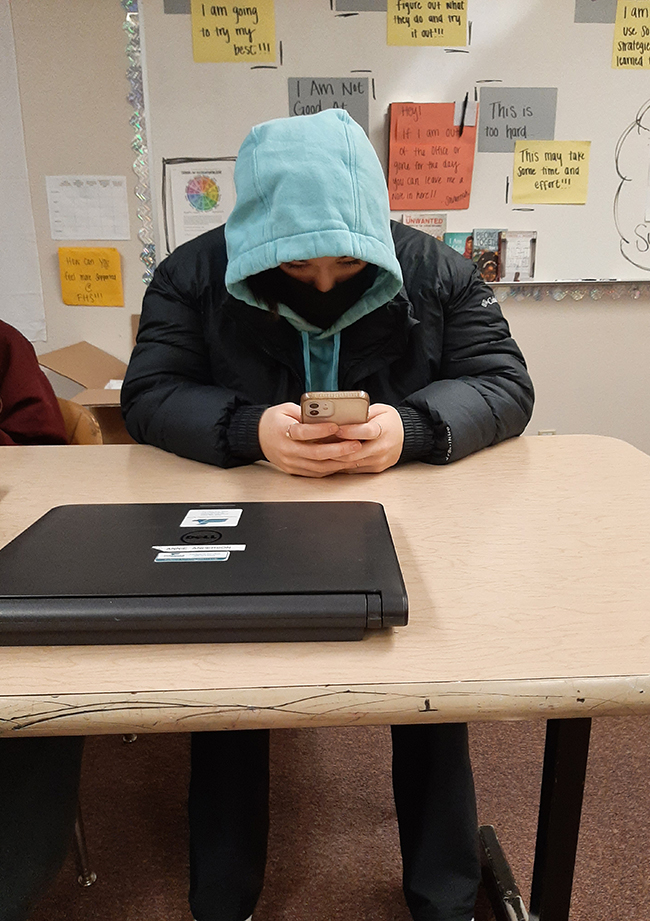

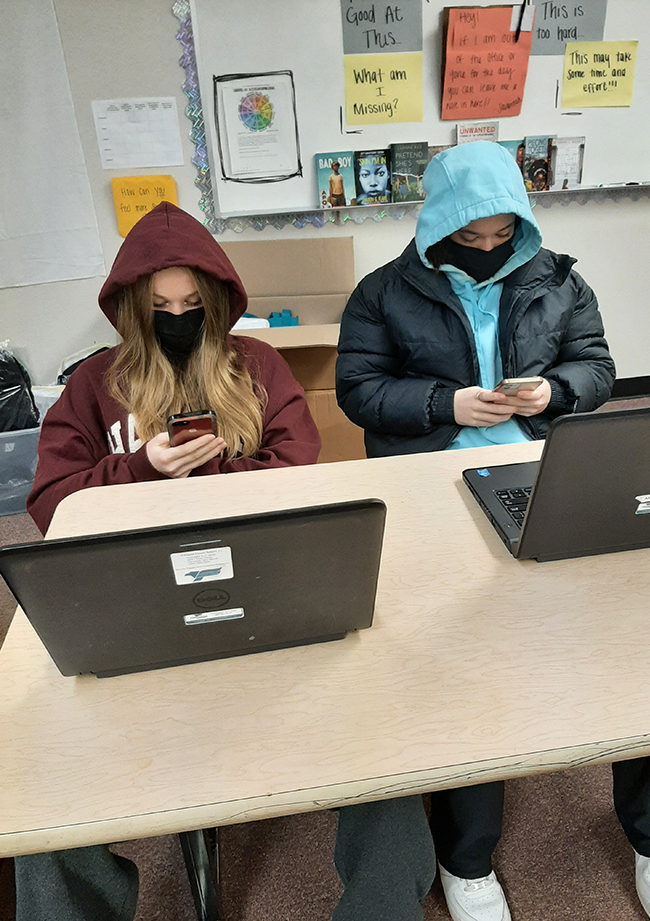

In the school setting we have made concessions surrounding policies regarding: Attendance, tardiness, student engagement, dress code, cell phone usage, academic requirements, behavioral expectations, etc. It has been widely recognized that many students are “behind”, in the sense that in-person, on site, classroom instruction was interrupted, and even replaced for a time. Foundational social, emotional, and academic skills were lost or are lacking. Anxiety, depression, and apathy are at an all-time high but, to make matters worse, so are barriers to relationships. The two primary relational barriers, in my opinion, are masks (some days it is difficult to see enough of a teenager’s face to even know who you are talking to) and student/parent/staff burnout. (When you can barely function yourself, it’s incredibly difficult to support, encourage, and care for another.)

So, while I absolutely understand the Why and How we got to this place, I worry that we may not be going about it in the right way. “It”, meaning how we help our children navigate the world that we are all currently experiencing. I would suggest that it isn’t through the lowering of standards or widely abused accommodations. I believe precisely because there has been so much change that our kids have had no control over, that we should keep as many previous expectations as possible. For example, your teen may have been doing online school in the comfort of their pajamas, with the flexibility of logging in and working at their leisure. Cool! (Who doesn’t love working in PJ’s?!) But they’re not remote learning any longer. Now the expectation is to show up, on time, dressed appropriately, and ready to learn.

Previously your teen may have passed their classes by demonstrating a minimal amount of “engagement” during the school week. That was then, this is now. Now the expectation is that they participate fully and turn in completed assignments, within a deadline, to pass their classes. (Is there any confusion as to which will better prepare them for a job and in life?!)

Your teen’s phone was a source of comfort while they were disconnected from friends, teachers, and activities so they were afforded the opportunity to use it during class while they reacclimated. That can’t and shouldn’t continue. Now it is time to put the phone down, to look at, and listen to, the people who are there to teach, help, and support them. Their future literally may depend on it.

There is no question the importance of validating what our teens have gone through, what they are continuing to go through, and the individual impact it is having on them. But rather than perpetuating messages about how unfair it was to miss out on friends and activities and “regular” school, and then, because of it, requiring less of our kids and excusing patterns of behavior that are not in their long-term best interest, what if we were to switch it up? What if we started treating kids like we believe they can handle hard things? What if we acknowledge that we understand they don’t like how things have been, but then reassure them that they will benefit from rising above and pushing through? Sometimes the Band-Aid just needs to be ripped off. Is it going to sting a little? Yep, it is. But the wound needs air because if it stays all covered up (“protected”) it won’t ever completely heal.

Life is happening the way it is happening. As parents and professionals, we have a choice to either continue making accommodation to try and mitigate the ongoing challenges which will, arguably, prolong valuable academic and personal skill development, or we rip off the Band-Aid. We wipe the tears and acknowledge the scrapes, and bumps along the way, and we help foster perseverance and resiliency. Rather than withdrawing, fearing change, and doubting their ability to cope, the hope is that our kids will feel confident, capable and prepared for what comes their way! I believe they will, just as soon as we start treating them like it.

Loved this article. The money line: “What if we started treating kids like we believe they can handle hard things?” I don’t see how we can get back on track if we don’t adopt that approach.

Thank you, Peggy. Kids are far more capable than we often give them credit for.