Compensation Parenting

Compensating is something that we all do. If you are someone who runs habitually late, you may try to compensate by setting your clock a half an hour ahead of the time it actually is. If we hurt our right foot, we compensate by putting more weight on our left foot until the right one heals. Compensating is often meant to create balance or to counteract a negative. Sometimes we intentionally compensate, and other times compensation happens without us consciously knowing it is happening.

As parents, we feel guilty if our children are lacking in some area. Especially difficult to acknowledge is if your child is being deprived of crucial foundational elements such as: stability, belonging, self-worth, closure or acceptance. Or maybe they are not meeting societal (or your) expectations regarding, athleticism, popularity, scholastic aptitude…Any of these concerns (and a multitude of others) can feel sizeable to a parent, especially if we believe our children are hurting because of it.

The problem with compensating is that after time it either becomes ineffective (you know you have an extra half an hour on the clock, so you don’t get moving right away which means you’re still late), or the problem just morphs into a different problem. (The foot heals, but the hip and back are now out of whack). We do this with parenting as well. All of us, in some form or another, compensate at some point. Sometimes we compensate for minor or isolated incidents and other times the compensation is chronic and in regard to deeper more complex issues.

An example of my own Compensation Parenting was when our daughter Presley was in the fourth grade. I worked at the elementary school my kids attended and was very aware that “puberty talk” day was coming up. Back then the kids were separated by gender and spoken to about “gender specific” topics in different classrooms. It was quite a big deal to the students and every year there was a buzz surrounding the anticipation of that particular day. When the consent form came home, I signed it and gave it back to Pres to return to school.

The day of the lesson, after we got home, I asked Presley how it went. And she started to cry! My first thought was “What on earth did they tell her about having a period??” Her reaction was not at all what I expected (or typical for her) so I was definitely concerned. When I asked her what happened, she told me that she didn’t get to go. I was so confused. “Why didn’t you get to go?” Well…apparently the form I signed was an Opt-Out form, not a consent form. Ugh… problematic on multiple levels. (Not reading what you sign for one!) Presley tried to assure her teacher that I wanted her to go but because I had signed the Opt-Out paperwork, and Mr. Diaz knew me to be a very intentional parent, he was not about to question my choice. So… off she went to the library with the other students whose parents opted them out, missing the entire lesson.

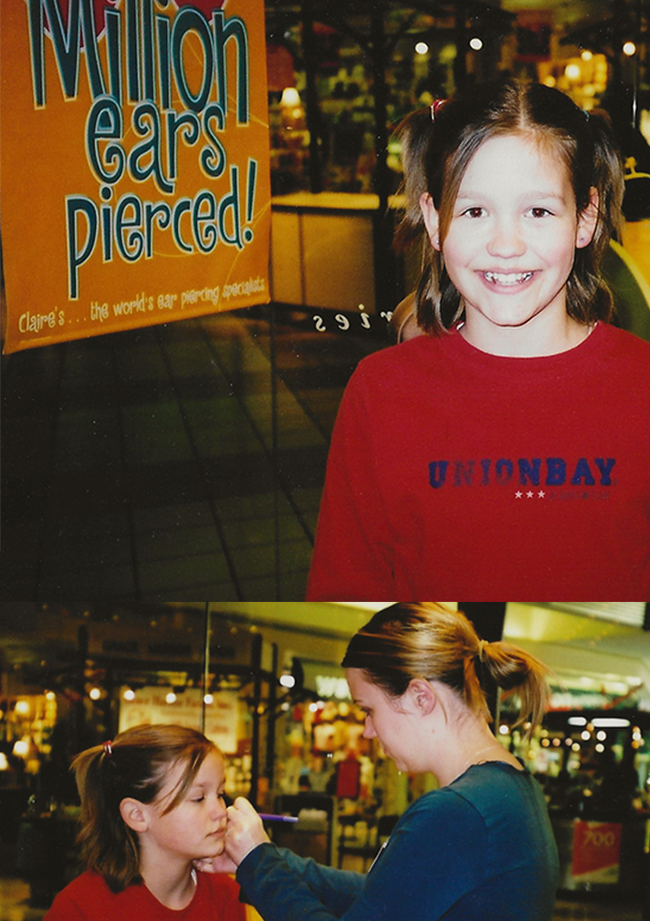

Compensate for my mistake? Darn right I did. Guess who got her ears pierced! I felt horrible about how upset Pres was, knowing she wanted to be there with all her friends at the “event”. So, we made an appointment for the ear piercing right away in an attempt to replace my bad-mom-moment with a mom-is-awesome memory. I had been saying NO to ear piercing previously, so this was the perfect compensation. (In the brain of a mom who was feeling guilty anyway…) That particular compensation was obviously very intentional. It was planned based on an isolated incident and served a purpose that worked in the way that I had intended it to. As an amends for my mistake, which thankfully ended Presley’s anger and sadness because she had new, cute studs poked into the holes in her ears that I purchased. No shame in my game that day!

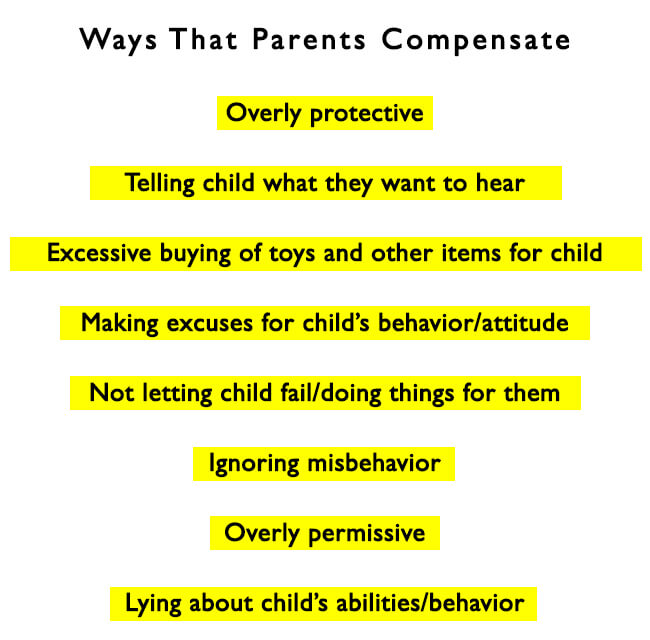

Compensation far more insidious is the type that we as parents may not be innately aware of. Life circumstances that create a pattern of parenting that drive the interaction and messages between a parent and child in a way that can be unhealthy or even harmful. Divorce, health issues (parents or child’s), adoption, the death of a parent, addiction, incarceration, physical/emotional factors, learning deficit, etc. When parents compensate long term for issues that are deep and complex it can lead to unhealthy outcomes because compensation does not address the core issue. It does not make up for what has been lost or their negative experience.

As parents, we want to “fix” whatever it is that keeps our kids from being happy. And when that is not possible, we often try to make up for it by compensating. Compensating is a band-aid and something we do primarily to attempt to make ourselves feel better. For isolated incidents (see puberty talk snafu above) it can work fine, but for more serious concerns it does not.

Using the examples I mentioned a couple of paragraphs earlier, the “fix” that your kids want is simply not always going to be possible. Sometimes that is the harsh, unfair, reality of life. Other times progress might be possible but it could require more effort than the child is willing to put forth (like with sports, frienships and school.) Rather than compensating, which will not change their circumstance and will only create secondary issues, try instead to simply support and validate the feelings they have about the situation. Support is being attentive while they vent, cry or question. Validation is acknowledging that their circumstance is hard for them and may even be unfair. Support is letting them know you are there to help them through it and that some days will be better than others.

At the end of the day, listening to your child, following their lead, and reassuring them that they will be ok, is of far greater service to them than any form of compensation will ever be.